Executive Summary

Medical negligence in South Africa is a complex, emotionally draining landscape where the law seeks to hold healthcare providers accountable for avoidable harm. This guide strips away the legal jargon to explain that “the standard of care” is a universal requirement, regardless of whether a patient is in a private or public facility. To win a claim, a patient must prove duty, breach, causation, and actual damages—a high bar that requires expert medical testimony and years of litigation.

The article explores common failures, such as birth injuries and surgical errors, while warning against the predatory practices of “ambulance-chasing” lawyers. It highlights the three-year prescription period, the reality of “no win, no fee” agreements, and the heavy emotional toll of a legal system that often prioritizes delay over resolution. Ultimately, the decision to sue should be based on a clear-eyed assessment of the evidence and a person’s capacity for a long-term legal battle. This resource serves as a roadmap for those seeking justice, emphasizing that while money cannot restore health, it is the only tool the law has to provide for a future altered by someone else’s mistake.

The Reality of the South African Healthcare Landscape

Two Systems, One Standard

South Africa is a country of deep contradictions. You see this most clearly in our hospitals. We have private facilities that look like five star hotels. We also have public wards where the paint is peeling and the queues stretch out the door. It is easy to assume that negligence only happens in the crowded public spaces. That is a dangerous lie.

I have seen horrific errors in the most expensive private clinics in Sandton and Cape Town. A shiny lobby does not guarantee a competent surgeon. A private room does not mean the nurses are monitoring your vitals. Money buys comfort. It does not always buy safety.

The law in South Africa does not care about the size of the hospital’s budget. It expects a certain level of care from every doctor. This is the “reasonable person” test. We ask if a reasonable doctor, in the same position, would have made that same choice. If the answer is no, the hospital is in trouble. It does not matter if they were short on bandages or had the latest laser equipment.

The standard stays the same. If a doctor chooses to operate, they must meet the standard of a surgeon. If a nurse monitors a labor, they must meet the standard of a midwife. The system tries to divide us by what we can afford. The law, at least in theory, tries to hold everyone to the same mark of human safety.

We have to stop thinking that luxury equals immunity. I have spoken to families who paid hundreds of thousands for a procedure only to be left with a permanent disability. They felt betrayed because they thought their money bought a guarantee. It did not. Negligence is a human failure, not a financial one.

Why Silence is the Default

When something goes wrong in a South African hospital, the air changes. The doctors who were once friendly suddenly stop making eye contact. The nurses start whispering at the end of the hallway. You are left sitting in a plastic chair, wondering why your life has just fallen apart. This silence is not accidental. It is a defense mechanism.

Medical professionals in this country are terrified of the legal system. They are taught, often by their insurers, to say as little as possible. They think that an apology is a confession. So, they give you technical jargon instead of the truth. They tell you there were “complications” when what they mean is that they nicked an artery.

This culture of silence is a secondary trauma for the patient. You are already hurting. Now, you are being ignored by the people you trusted with your life. It makes you feel like you are losing your mind. You know something is wrong, but the experts are gaslighting you.

I have seen cases where a simple, honest conversation could have prevented a lawsuit. But the ego of the profession gets in the way. Doctors find it hard to admit they are capable of making a mistake. They are viewed as gods for so long that they start to believe it themselves. When the god fails, they hide.

You need to understand that you are not imagining the coldness. It is a wall built to protect the hospital’s bottom line. Breaking through that wall requires more than just asking nicely. It requires a realization that the person who hurt you is now your legal adversary. That is a hard pill to swallow when you are still bleeding.

What Negligence Actually Looks Like (Beyond the Jargon)

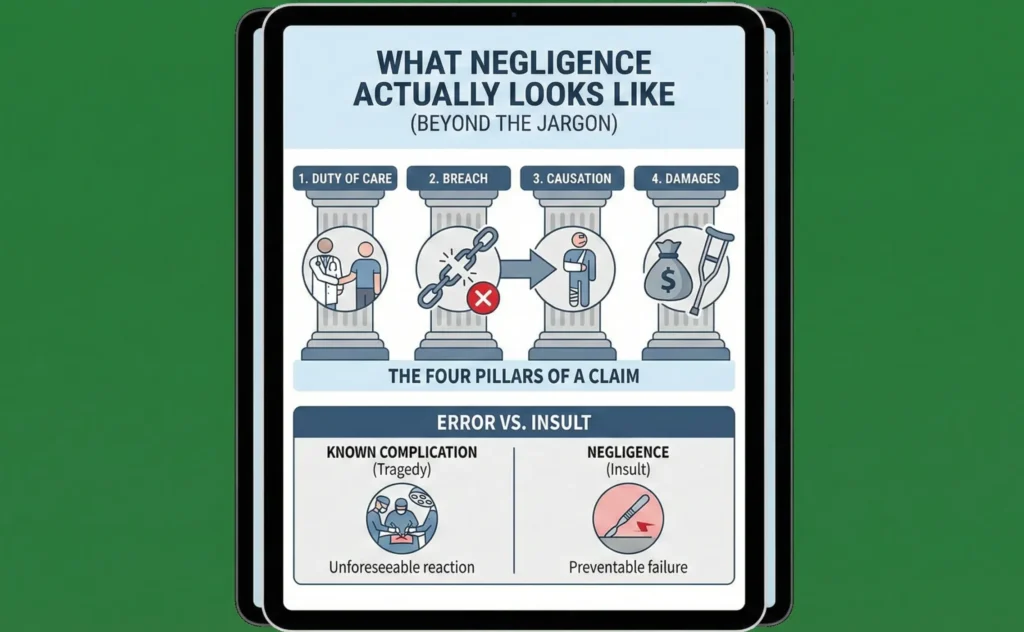

The Four Pillars of a Claim

Lawyers love to hide behind Latin words like lex aquilia or iniuria. It makes them feel important. But when you are sitting in a wheelchair or grieving a parent, you do not need a history lesson. You need to know if you have a case. To win a medical negligence claim in South Africa, you generally have to prove four things.

First, there is the duty of care. This is the easy part. If you walk into a clinic or check into a hospital, a relationship is formed. The doctor or the facility now has a legal obligation to look after you. They cannot simply ignore your deteriorating state. Once you are their patient, they are on the hook for your safety.

Second, we look for the breach. This is where the fighting starts. Did the medical professional do something they should not have done? Or did they fail to do something they should have? We compare their actions to a hypothetical “reasonable” professional. We don’t expect them to be perfect. We just expect them not to be careless.

Third, we have to prove causation. This is the brick wall many cases crash into. You might prove the doctor was a complete idiot. You might prove he was drunk. But if the injury you suffered would have happened anyway because of your underlying illness, you have no case. You have to prove that his mistake actually caused the harm.

Finally, there are damages. You must have suffered a real loss that can be measured in money. If a doctor makes a massive mistake but you walk away completely fine, you cannot sue. The law does not punish people for “almost” hurting you. It only steps in when there is a bill to be paid or a life that has been altered.

The Difference Between an Error and an Insult

Not every bad outcome is negligence. This is a bitter truth to hear. Surgery is inherently dangerous. Drugs have side effects that no one can predict. Sometimes, despite the best efforts of the best doctors in the world, the patient dies or loses a limb. The law calls these “known complications.”

I think of negligence as an insult to the profession. It is the difference between a surgeon’s hand slipping during a freakishly difficult procedure and a surgeon leaving a pair of scissors inside your abdomen. One is a tragedy of biology and physics. The other is a failure of basic human attention.

I once looked at a case where a woman lost her sight after a routine eye surgery. It was devastating. But every expert we spoke to said the same thing. It was a one-in-a-million reaction to the anesthesia. No one could have seen it coming. No one did anything wrong. It was just a horrible, random stroke of bad luck.

The legal system is not an insurance policy for bad luck. It is a system for accountability. If a nurse sees a patient’s oxygen levels dropping and decides to finish her tea before checking on them, that is an insult. That is negligence. We have to be honest enough to separate the two, even when it hurts.

Before you spend years of your life in court, you have to ask yourself a hard question. Was this a mistake that any doctor could have made in a moment of extreme pressure? Or was this a systemic failure of care? The answer to that question determines whether you are seeking justice or just seeking someone to blame for the unfairness of life.

The Most Common Failures in South African Wards

Childbirth and Cerebral Palsy

There is no pain like the pain of a parent who realizes their child’s brain has been starved of oxygen. In South Africa, birth injury cases fill our court rolls. Most of them follow the same haunting pattern. A mother goes into labor. She is healthy. The baby is healthy. Then, the system fails.

These cases usually revolve around the CTG machine—the monitor that tracks the baby’s heart rate. In a busy public hospital, there might be one nurse for ten laboring women. The monitor starts to show “fetal distress.” The baby is struggling. But the nurse is in the next room, or she is tired, or she simply does not know how to read the graph.

By the time the doctor is called, it is too late. The baby is born blue and silent. This is often “hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy” or HIE. It leads to cerebral palsy. It means a lifetime of 24-hour care, wheelchairs, and feeding tubes. It is almost always preventable if the delivery happened twenty minutes sooner.

The tragedy is that the hospital often tries to blame the mother. They point to her nutrition or a “silent infection.” They do this to avoid the massive payouts these cases require. A cerebral palsy claim can be worth thirty million Rand or more because the child will need care for sixty years. The State fights these cases with a desperation that borders on the cruel.

I have sat with these mothers. They carry a guilt that is not theirs to own. They think they should have screamed louder. They think they should have known something was wrong. But they were the ones in the hospital bed, not the ones with the medical degree. The failure belongs to the institution, not the parent.

Surgical Blunders and Retained Instruments

We like to think of the operating theater as a place of sterile, perfect precision. The truth is much more chaotic. Surgeons are often overworked. They are human. They get distracted. Sometimes, they close the incision and leave something behind.

It sounds like an urban legend, but I have seen the X-rays. Gauze swabs, needles, and even metal clamps left inside a human body. The patient goes home, but the pain never stops. They develop infections. They are told it is just “normal post-op recovery.” Months later, a scan reveals a foreign object festering near an organ.

This is what the law calls res ipsa loquitur—the thing speaks for itself. There is no “reasonable” excuse for leaving a surgical tool inside a patient. It happens because the surgical team failed to count. They didn’t check the tray before they started, and they didn’t check it before they finished.

It is a failure of basic protocol. In many South African hospitals, the pressure to “clear the list” of surgeries leads to these shortcuts. When speed becomes more important than the checklist, people get hurt. If you have had surgery and the pain feels “wrong” or an incision won’t heal, do not let them tell you it is in your head.

Misdiagnosis and the Cost of Lost Time

Time is the only currency that matters in medicine. If you have a stroke, you have a window of hours. If you have cancer, you have a window of months. In South Africa, people die in the waiting rooms of the system because they were sent home with Panado when they actually had meningitis.

Misdiagnosis is hard to prove because doctors are allowed to be wrong. They are allowed to have a “differential diagnosis” where they test for the most likely thing first. But they are not allowed to be negligent. If a patient presents with every classic symptom of a heart attack and the doctor ignores it because the patient is young, that is a failure.

I see this often with TB and oncology. A patient has a cough that won’t go away. The clinic treats them for a cold. Six months later, it turns out to be a massive tumor. By then, it is stage four. The “lost window” is the negligence. Had they acted on day one, the patient might have lived.

You have to be your own advocate in this system. If you feel that a doctor is dismissing your symptoms because they are too busy to listen, you are probably right. The legal struggle here is proving that the delay actually changed the outcome. It is a grim calculation of “what might have been” if the doctor had just done their job.

The Legal Gauntlet: How the Process Works

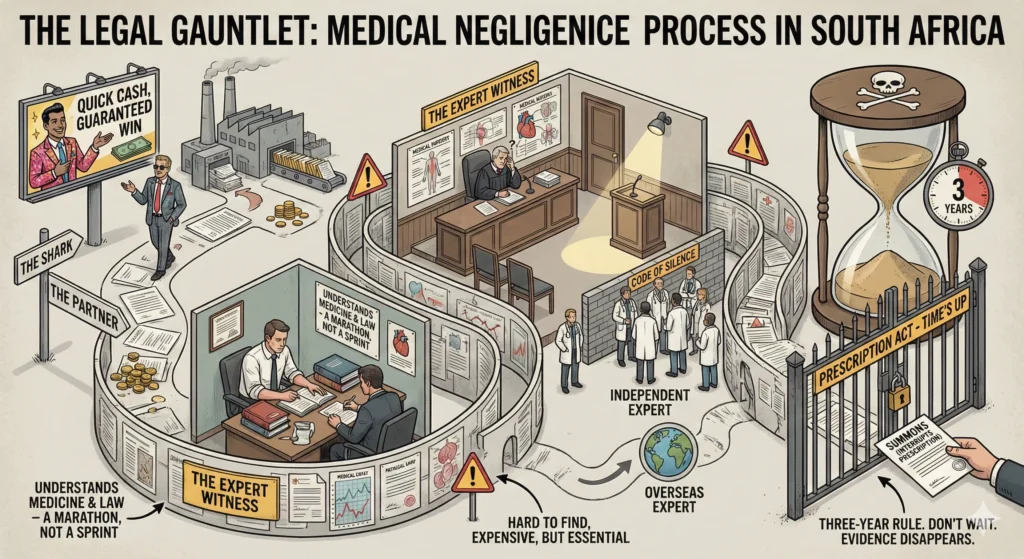

Finding a Lawyer Who Isn’t a Shark

The moment you realize you have been wronged, you will be tempted to call the first name you see on a billboard. Do not do that. The world of medical negligence law in South Africa is full of people who see your tragedy as a payday. Some firms operate like factories. They take on thousands of cases, settle them for the first low offer the State makes, and move on to the next victim.

You need to find someone who actually understands medicine. A good lawyer in this field should be able to read a pathology report or an obstetric graph almost as well as a doctor. If they cannot explain the science of your injury to you in plain English, they cannot explain it to a judge. Ask them how many cases like yours they have actually taken to trial. If they only settle, they aren’t fighters. They are brokers.

Be careful of the “guarantee.” No honest lawyer can promise you a win. The law is too unpredictable. If someone tells you your case is a “slam dunk” before they have even seen your hospital records, walk away. They are telling you what you want to hear so you will sign their fee agreement. You need a partner, not a salesman.

I have seen families get stuck with lawyers who stop answering the phone after a year. These cases are marathons. You are going to be in a relationship with this legal team for three, five, or maybe eight years. You need to trust them. You need to feel like a human being in their office, not just another file number.

The Role of the Expert Witness

In a South African courtroom, a judge is an expert on the law, not on the human body. They cannot decide if a surgery was botched just by looking at the scars. To win, we have to bring in other doctors to testify. These are called expert witnesses. This is the hardest part of the entire process.

South Africa is a small country. The medical community is tight. Doctors go to the same universities and belong to the same professional bodies. Many of them are terrified of being labeled a “traitor” for testifying against a colleague. There is an unwritten code of silence. If you are suing a neurosurgeon in Johannesburg, it is often very hard to find another Johannesburg neurosurgeon willing to stand up and say their peer was negligent.

We often have to look for retired specialists or experts from other provinces. Sometimes we even have to go overseas. These experts are expensive. They charge for every hour they spend reviewing your files and every hour they spend sitting in court. But without them, your case is dead on arrival.

The expert’s job is to be objective. If an expert tells us that the doctor actually followed the correct protocol, we have to listen. A lawyer who tries to “buy” a favorable opinion from a shady expert is doing you no favors. The judge will see through it, and you will lose. You need the cold, hard truth from a professional who is respected by their peers.

Timelines and the Prescription Act

Time is not your friend. In South Africa, the general rule is that you have three years from the date of the negligence to file your claim. This is called “prescription.” If that clock runs out, your right to sue vanishes forever. It does not matter how bad the injury was. The law simply closes the door.

There are some exceptions, mostly for children. For a minor, the three-year clock only starts ticking once they turn eighteen. However, waiting that long is a massive mistake. Evidence disappears. Hospital records get “lost” in a basement flood. Nurses move away or die. Witnesses forget the details of that specific night in the ward.

I have seen people come to me three years and one month after an incident. Their stories are heartbreaking. Their injuries are obvious. But my hands are tied. The State will raise a “special plea of prescription” immediately, and the case will be thrown out before it even starts. It is a brutal, heartless rule, but it is the law.

As soon as you suspect something went wrong, start moving. You don’t have to sue immediately, but you need to get your “summons” served. This “interrupts” prescription and protects your rights. Do not let a hospital administrator string you along with promises of an “internal investigation” until the three years are up. That is a common tactic to run down the clock.

The Money: Damages and Costs

Contingency Fees and the 25% Rule

Most people I talk to are terrified of the cost. They see the high-rise offices and the expensive suits and think, “I can’t afford justice.” This is why the Contingency Fees Act exists. It allows for a “no win, no fee” arrangement. It is a gamble for the lawyer, and a lifeline for the patient.

But you need to read the fine print. By law, an attorney can only charge a maximum of 25% of your total payout, or double their normal hourly rate—whichever is lower. I have seen some lawyers try to take 40% or 50% by adding “administrative fees” or “success bonuses.” That is illegal. It is predatory.

You also need to ask who pays for the experts. A single case might require a neurologist, a radiologist, an actuary, and an industrial psychologist. These reports cost thousands of Rand each. If the lawyer is paying for them upfront, they are taking a risk. If you lose, they lose that money. That is why they are so picky about which cases they take.

I always tell people: if a lawyer asks you for a “deposit” for a medical negligence case, be careful. If the case is strong, the lawyer should be willing to back it with their own firm’s capital. If they aren’t, it might mean they don’t actually believe you can win. Or it means they don’t have the resources to go the distance.

What “Damages” Actually Mean

People often hear about “millions” in the news and think it’s like winning the lottery. It isn’t. In a medical negligence claim, the money is divided into different buckets. The first bucket is “Special Damages.” This is for money you have already spent or will definitely spend on doctors, therapies, and equipment.

Then there is “Loss of Earnings.” If you were a builder and now you can’t walk, the court calculates what you would have earned until you retired. We use experts called actuaries to do this math. They adjust for inflation and interest. It’s cold and clinical. They turn your working life into a spreadsheet.

The final bucket is “General Damages.” This is for pain, suffering, and the “loss of amenities of life.” This is the only part of the money that is actually meant to compensate you for the misery. In South Africa, these payouts are surprisingly low compared to the US or UK. A judge might give you R500,000 for a permanent, life-altering injury.

It never feels like enough. No amount of money can replace a limb or a child’s health. The money is just there to stop the bleeding—to make sure you don’t end up on the street because you can’t work. It is a calculated, imperfect attempt to put a price on something that is priceless. It’s a bitter realization when the check finally arrives.

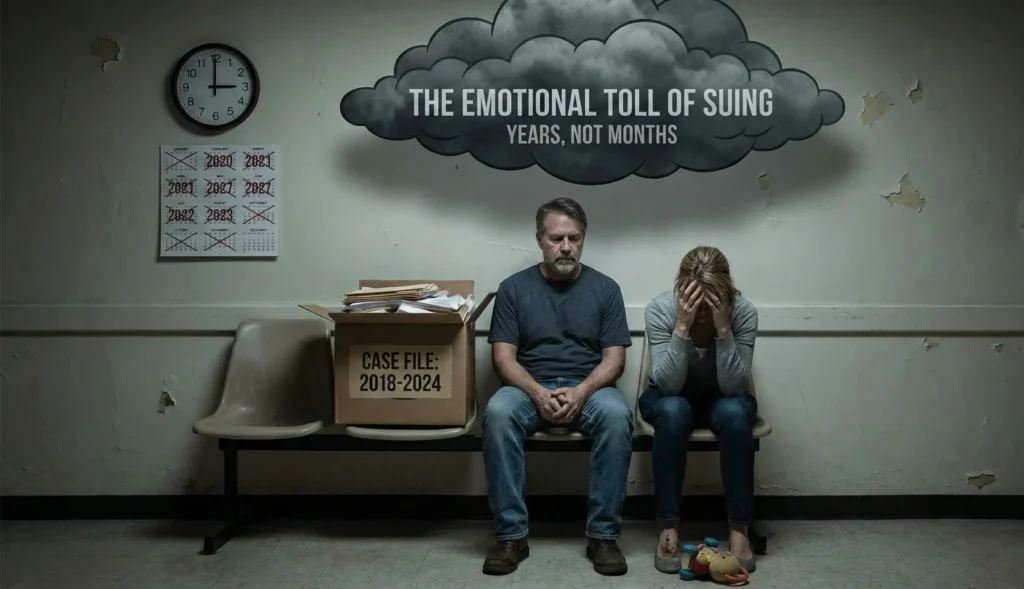

The Emotional Toll of Suing

Why It Takes Years, Not Months

If you are looking for a quick resolution, the South African legal system will break your heart. This is not a TV drama where the case is wrapped up in an hour. It is a slow, grinding war of attrition. You are looking at a minimum of three to five years, and if the State is involved, it can easily stretch to a decade. This delay is often used as a weapon against you.

The defendants—usually the Provincial Department of Health or a private hospital’s massive insurance company—have deep pockets. They are not in a hurry. They will delay by asking for more documents. They will postpone meetings. They will wait until the very last day of a deadline to file a response. They hope that as the years pass, you will get tired, get desperate for money, and settle for a fraction of what you deserve.

I have seen families fall apart during this wait. The initial anger that fueled the lawsuit turns into a dull, heavy exhaustion. You have to keep reliving the worst day of your life every time a new lawyer or expert asks you a question. You are stuck in a waiting room that spans years. You cannot move on because the case is always there, looming over your future like a dark cloud.

You must prepare yourself for this. Do not plan your life around a payout that might not come for half a decade. You have to find a way to live, breathe, and heal while the legal machine turns its slow gears in the background. If you go into this thinking it will be over by Christmas, you are setting yourself up for a secondary trauma.

Dealing with the Guilt

There is a specific kind of silence that happens when a parent talks about a birth injury. Beneath the anger at the hospital, there is often a poisonous layer of self-blame. I have heard mothers ask if they should have driven to a different hospital, or if they should have noticed the baby stopped moving sooner. They feel they failed in their most basic job: to protect their child.

If you are feeling this, listen to me. You are not a doctor. You are not a midwife. You went to a hospital because that is where the experts are supposed to be. You trusted the system because that is what we are taught to do. The failure of a professional to do their job is not your fault. You cannot hold yourself responsible for someone else’s incompetence.

The legal process doesn’t help with this guilt. In fact, the hospital’s lawyers might try to use it against you. They might ask why you didn’t seek help sooner or why you didn’t follow a specific instruction perfectly. It is a tactic to shift the blame. It is meant to make you doubt yourself so you become a “weak” witness.

Healing from medical negligence is about more than just a court order. It is about forgiving yourself for being a human who couldn’t see the future. You were the victim of a breach of trust. The person who should be feeling guilty is the one who walked away from your bed when the monitor started beeping. Not you.

The Road Ahead: Making the Decision

When to Walk Away

I am going to say something that many lawyers will hate. Sometimes, the best thing you can do for your sanity is to walk away. Not every error is a lawsuit. Not every injury, however painful, is a viable claim in the South African courts. If the cost of the experts and the years of emotional labor outweigh the potential payout, a “victory” can feel like a loss.

Lawyers call these “nuisance value” cases. Maybe a nurse was rude, or a doctor made a mistake that caused you two weeks of extra pain but no permanent damage. In these instances, the system is not designed to help you. You will spend R100,000 on experts to win R50,000 in damages. It is a mathematical trap. If your lawyer is honest, they will tell you when the juice isn’t worth the squeeze.

You also have to consider the “litigation lifestyle.” For the next five years, your injury will be your identity. You will be poked by doctors who are paid to find nothing wrong with you. You will be questioned by lawyers who want to make you look like a liar. If you are already at your breaking point, adding a high-stakes legal battle might be the thing that finally snaps you.

There is a dignity in choosing peace over a payout. It is not “giving up.” It is a calculated decision to protect your remaining quality of life. Justice is a noble goal, but it is a cold one. It doesn’t always provide the closure you think it will. Sometimes, the only way to truly win is to refuse to play the game.

Taking the First Step

If you have weighed the risks and decided to move forward, you need to act with precision. Do not rely on your memory. Trauma has a way of blurring the edges of time. Sit down tonight and write a “Statement of Events.” Start from the moment you walked into the hospital until the moment you realized something was wrong.

Who did you speak to? What did the nurse say at 2:00 AM? Did anyone apologize? These small details are the seeds of a successful case. Once you have your story down, get your medical records. You have a legal right to them under the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA). Do not let the hospital tell you the files are “private.” They are yours.

Once you have your notes and your records, find a specialist. Do not go to a general practitioner lawyer who handles divorces and car accidents. You need a medical negligence specialist. Show them what you have gathered. If they are good, they will be cautious. They will tell you the truth, even if the truth is that your case is difficult.

This is the start of a very long walk. It begins with a single phone call or a single email. Before you make it, take a deep breath. Make sure you are doing this for the right reasons. If you are doing it for the money, you might be disappointed. If you are doing it for accountability, for the truth, and to ensure this doesn’t happen to someone else, then you are ready.

Conclusion

The South African medical system is a place of incredible skill and devastating failure. If you find yourself on the wrong side of that failure, you are likely feeling a mixture of grief and a burning need for someone to say, “I am sorry, this was our fault.” In our current legal climate, you will rarely hear those words. Instead, you will find a system that is designed to protect itself.

Suing a doctor or a hospital is not an act of malice. It is an act of holding the powerful to the same standards as the rest of us. It is about making sure that when a life is broken by carelessness, the person responsible bears the cost of the repair. It is a difficult, uphill climb, but for many, it is the only path to a stable future.

If you believe you or a loved one has suffered due to medical negligence, do not sit in silence. The clock is already ticking. Reach out to a qualified legal professional today to discuss your options. You deserve to have your story heard, and more importantly, you deserve to know the truth about what happened in that hospital room.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How do I know if I have a "good" case?

A “good” case usually has three things: clear evidence that a doctor deviated from standard practice, a permanent or serious injury, and a direct link between that mistake and the injury. If you were hurt but recovered fully in a week, the “value” of the case might be too low for a lawyer to take on contingency.

2. Can I sue a government hospital?

Yes. You sue the Member of the Executive Council (MEC) for Health in that province. However, you must give the State “notice of intended legal proceedings” within six months of the incident. If you miss this, you have to ask a judge for special permission to continue.

3. What if I signed a consent form? Does that mean I can't sue?

A consent form is not a “get out of jail free” card for a doctor. You consent to the known risks of a procedure, not to negligence. If a surgeon is careless, a piece of paper doesn’t protect them from the law.

4. How much will I actually get paid?

It depends on your age, your job, and the severity of the injury. Most of the money goes toward future care and loss of earnings. “Pain and suffering” payouts in South Africa are relatively modest, often ranging from R100,000 to R800,000, depending on the trauma.

5. How long do I have to start a claim?

Generally, three years from the date you became aware of the negligence. For children, the clock technically starts at age 18, but you should never wait that long as evidence disappears.

6. Do I have to pay my lawyer upfront?

If you sign a contingency fee agreement, you usually don’t pay anything upfront. The lawyer takes the risk and gets paid a percentage (capped at 25%) only if you win.

7. Can I sue if my baby was born with Cerebral Palsy?

Yes, if the condition was caused by a lack of oxygen during labor that the staff failed to monitor or act upon. These are the most common and highest-value claims in South Africa.

8. What if the doctor apologized? Is that an admission of guilt?

In South Africa, an apology isn’t always a legal admission of negligence, but it is rare. Most doctors are told by insurers not to apologize, which is why the system feels so cold.

9. Can I get my medical records if the hospital is refusing?

Yes. Under the PAIA Act, you have a legal right to your records. A lawyer can help you draft a formal request that the hospital cannot legally ignore.

10. What is an "expert witness"?

It is a doctor or specialist who reviews your file and tells the court whether your treating doctor followed the correct rules. You cannot win a case without one.

11. How long does a medical negligence case take?

Expect a minimum of 3 to 5 years. If the State is defending the case, it can take much longer. It is a test of endurance.

12. Will I have to go to court and testify?

Most cases settle before they reach a full trial, but you must be prepared to testify. You will have to tell your story and be questioned by the other side’s lawyers.

13. What if I can't remember exactly what happened?

This is common. Trauma affects memory. This is why we rely heavily on the hospital’s clinical notes, which are written at the time of the event.

14. Can I sue for a "near miss"?

No. If a doctor almost made a fatal mistake but caught it in time and you are fine, there are no “damages.” The law only compensates for actual harm.

15. What is the "Reasonable Doctor" test?

The court asks: “Would a reasonably competent doctor in the same branch of medicine have done the same thing?” If the answer is yes, it’s not negligence, even if the outcome was bad.

16. Can I switch lawyers if I’m unhappy?

Yes, but it’s complicated. Your first lawyer will likely have a “lien” on your file, meaning they want to be paid for the work they’ve already done before they hand the file over.

17. Why is my lawyer taking 25% of my money?

This covers their expertise and the massive financial risk they took by paying for experts and working for years without a paycheck. It is regulated by the Contingency Fees Act.

18. What happens if I lose the case?

In a true “no win, no fee” deal, you shouldn’t owe your lawyer their fees. However, in some cases, the court might order you to pay the other side’s legal costs. You must discuss this risk clearly with your attorney.

19. Can I sue for a misdiagnosis?

Only if the misdiagnosis was “negligent”—meaning a competent doctor should have caught it—and the delay in treatment caused you real, measurable harm.

20. What should I do right now?

Write down everything you remember. Get your hospital records. Then, find a specialist medical negligence attorney for a consultation. Don’t wait.