Executive Summary

In South African law, a tragic medical outcome does not automatically equal negligence. This article strips away the misconception that pain constitutes evidence. The courts do not demand perfection from doctors, only the standard of the “reasonable expert”—average competence. If a competent doctor could have made the same mistake, the case fails.

Success hinges on overcoming technical hurdles, primarily “Causation.” You must prove that the injury would not have occurred but for the doctor’s specific error. If the damage was inevitable due to underlying illness, the doctor is not liable. Furthermore, the legal maxim Res Ipsa Loquitur (“the thing speaks for itself”) rarely applies; the burden rests entirely on the patient to explain the mechanics of the failure using logic and expert testimony.

Litigation is not a path to quick justice. It is a grueling, expensive process often lasting 3 to 5 years. It involves invasive cross-examination and significant financial risk. This guide serves as a reality check: the legal system is a cold engine of logic, not a hospital for emotional validation.

It Is Not Enough That You Were Harmed

You are hurt. Something went wrong in that hospital room, and now your life is different. Maybe you are in pain. Maybe you can’t work. Maybe you lost someone you love. It feels obvious that someone should pay for this.

But here is the hard truth. In South African law, a bad outcome does not mean the doctor was negligent. You can walk into a surgery healthy and come out paralyzed, and the doctor might not be liable for a single cent. The law is cold. It does not look at your pain and work backward to find a culprit. It looks at the doctor’s actions and asks if they broke the rules.

This area of law falls under the Law of Delict. It is a dry, technical way of dealing with human tragedy. To win, you have to prove that the doctor did not just fail, but that they failed in a way no competent doctor would have. If you cannot prove that, you lose. It does not matter how terrible your injury is.

The difference between a bad outcome and a legal wrong

Medicine is dangerous. Every time a surgeon cuts into a body, there is a risk. Infections happen. Nerves get cut. People die on the table. These are known risks. They are the dark side of medicine.

A “medical accident” is when one of these risks happens despite the doctor doing their job properly. Negligence is different. Negligence is when the doctor ignores the rules. Negligence is sloppiness.

Think of it like driving a car. You can drive perfectly, follow every speed limit, and still hit a patch of oil and crash. That is an accident. But if you are texting while driving and you crash, that is negligence. The crash looks the same. The car is wrecked either way. But the law only punishes the driver who was texting. In court, we have to figure out if your doctor hit a patch of oil or if they were looking at their phone. Most of the time, it’s just oil. That is a hard thing to hear.

Why your anger does not count as evidence

You are probably furious. You want the judge to feel what you feel. You want the court to look at the photos of the damage and scream in horror. They won’t. Judges are trained to ignore emotion. They view sympathy as a distraction.

In a medical negligence trial, the courtroom feels like a laboratory. It is sterile. They will talk about your body like it is a broken engine. They will use Latin terms. They will debate percentages. Your anger, your tears, and your frustration are irrelevant to the legal test. They are real to you. But they are not evidence.

If you go into this expecting the court to validate your suffering, you will be disappointed. The court is only interested in one thing. Did the doctor deviate from the standard of good practice? Everything else is noise.

The Golden Rule: The Reasonable Doctor

The law does not care about what your doctor could have done. It cares about what a “reasonable” doctor would have done. This is the yardstick. Everything in your case will be measured against this imaginary person. It is the most important concept in medical law.

Who is this imaginary “reasonable” person?

In South Africa, the courts use a test called the “reasonable expert” test. They invent a fictional doctor. This fictional doctor is not a genius. He is not the best surgeon in Cape Town. He is not a pioneer who writes textbooks.

He is average. He is competent, but ordinary. He is careful, but not obsessive. The court looks at your doctor and asks a simple question. Would the average, competent doctor have made the same mistake? If the answer is “yes,” then your doctor was not negligent. Even if you are permanently damaged.

This feels unfair. When we are sick, we want Dr. House. We want a miracle worker. But the law does not demand miracles. It demands average competence. If your doctor was merely “okay,” that is usually enough to avoid jail or a lawsuit.

We do not expect perfection

Doctors are human. They get tired. They misread signs. They make judgment calls that turn out to be wrong. The law protects them when they do this.

There is a difference between being negligent and being wrong. A doctor can diagnose you with the wrong disease, treat you for it, and harm you. But if a reasonable doctor, looking at the same symptoms, could have made the same mistake, you lose. This is called an “error of judgment.” Courts are very forgiving of errors of judgment.

They know that medicine is not mathematics. It is a guessing game half the time. If the doctor was careful, thought about it, and just guessed wrong, that is not a crime. It is just bad luck. You cannot sue for bad luck.

The specialist vs. the GP

The bar moves depending on who you are suing. If you go to a General Practitioner (GP) in a rural clinic, the court expects a certain level of skill. It is a basic level. They do not expect him to spot a rare tropical brain fungus. If he misses it, he is probably safe.

But if you go to a specialist neurologist in a private hospital, the rules change. He calls himself an expert. He charges expert rates. So the court holds him to a higher standard. He should spot the fungus. If he misses it, he is in trouble.

You cannot hold a GP to the standard of a specialist. But you can hold a specialist to the fire. The more they claim to know, the less room they have to screw up.

| Feature | The General Practitioner (GP) | The Specialist |

|---|---|---|

| The Benchmark | The "Reasonable Doctor". Expected to have a broad but basic level of knowledge. | The "Reasonable Expert". Expected to possess high-level, specialized skills in a specific field. |

| Expectations | To diagnose common illnesses and know when a case is beyond their skill level. | To be up-to-date with the latest global research and complex surgical techniques in their niche. |

| The Margin for Error | Wider. They are not expected to spot rare, "textbook" complications immediately. | Narrower. Because they charge more and claim expertise, the law is far less forgiving of "missed" signs. |

| When they are Negligent | When they fail to refer a patient to a specialist when a reasonable GP would have realized it was necessary. | When they fail to perform at the level of their peers in that specific specialty (e.g., a neurosurgeon vs other neurosurgeons). |

The Court Is Not A Hospital (How Judges Think)

When your case finally gets to trial, you will walk into a room full of people speaking a strange language. They are not talking about healing. They are talking about liability. The judge sitting up on the bench is the most powerful person in the room. But here is the scary part. That judge probably hasn’t taken a biology class since high school.

Judges are not doctors

They are lawyers who got promoted. They know the Constitution. They know the rules of evidence. But they do not know how to perform a C-section. They cannot look at an X-ray and tell you if the bone was set correctly.

This is a massive problem. How can a judge decide if a neurosurgeon was negligent if the judge doesn’t understand neurosurgery? They have to be taught. Your trial is basically a classroom. The lawyers and the witnesses spend days teaching the judge Medicine 101. If they explain it badly, or if the judge misunderstands a complex medical concept, you lose. It is that fragile.

The battle of the experts

Because the judge doesn’t know the medicine, both sides hire mercenaries. We call them “expert witnesses.” You will hire a professor to say the doctor was incompetent. The doctor’s insurance company will hire a different professor to say the doctor was brilliant.

These experts are expensive. They charge by the hour. And they almost never agree. You might think medicine is a science with clear answers. It isn’t. It is full of gray areas. Your expert says “X.” Their expert says “Y.” They are both highly qualified. They both have fancy degrees. The judge sits in the middle, confused, trying to figure out which professor is telling the truth. It is a mess. And it is why these cases cost millions to fight.

Logic over credentials (The Linksfield Rule)

For a long time, judges just believed whichever doctor had the longest CV. If the expert was a big deal, the judge nodded and agreed. That changed with a famous case called Michael and Another v Linksfield Park Clinic. It changed the game.

The court decided that it doesn’t matter how famous the expert is. It matters if their story makes sense. The judge is allowed to say: “I am not a doctor, but your logic is flawed.” If an expert says something that defies common sense (or if they can’t back up their opinion with logical reasoning) the judge can throw it out. They don’t have to bow down to the medical profession anymore. Logic is king. If the doctor’s explanation doesn’t add up, the court can reject it. Even if a room full of specialists says otherwise.

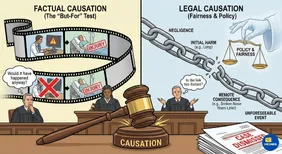

The Causation Trap: Where Most Cases Die

You can prove the doctor was incompetent. You can prove they broke every rule in the book. You can prove they were drunk on the job. And you can still lose your case completely. This is the part that drives victims insane. It is called “Causation.”

In South African law, proving negligence is only step one. Step two is proving that the negligence actually caused the damage. This sounds obvious. But it is the hardest hurdle in the entire legal system. Defense lawyers build their entire careers on this trap.

The “But-For” Test explained simply

The court uses a logical tool called the “But-For” test (or conditio sine qua non). The judge asks a strange, hypothetical question. “But for the doctor’s negligence, would the patient still be injured?” They mentally remove the doctor’s mistake from history and replay the movie.

If the movie ends the same way without the mistake, the doctor is innocent. It doesn’t matter that he was negligent. His negligence didn’t make a difference. The injury was going to happen anyway. The law refuses to punish a doctor for a harmless error.

When the damage would have happened anyway

Imagine a patient goes to the ER with a massive brain bleed. The doctor is lazy. He doesn’t order a CT scan. He sends the patient home with painkillers. The patient dies two hours later. This looks like clear negligence.

But at trial, the defense experts speak up. They say: “Even if the doctor had operated immediately, the bleed was too big. The patient was dead on arrival.” If the judge believes that, the case is over. The doctor’s laziness didn’t kill the patient. The brain bleed did. The doctor was negligent, yes. But he is not liable for the death. He walks away. This happens all the time. They blame the underlying disease. They blame your body.

Factual causation vs. Legal causation

There is a second layer to this mess. Even if you prove the doctor caused the harm, the link cannot be too weird or distant. This is called “Legal Causation.” The court asks if it is fair to hold the doctor responsible for everything that followed.

If a doctor sets a broken leg badly, he is liable for the limp. But if you trip because of that limp five years later and break your nose? The court will probably say that is too remote. The chain of liability has to end somewhere. Judges use policy and fairness to cut the chain. They decide where the doctor’s responsibility stops and where your bad luck begins.

The “Silence” Problem: Informed Consent

Sometimes the surgery goes perfectly. The hands of the surgeon were steady. The procedure was textbook. But you are still furious because you ended up with a complication you didn’t know was possible. You feel tricked. You say: “If I knew this could happen, I never would have agreed to the operation.” This is the battlefield of Informed Consent.

In South Africa, silence can be negligence. It is not enough for a doctor to be good with a scalpel. They have to be good with their words. They have to tell you the truth before they touch you.

Did you know the risks?

Most people think “consent” is that form you sign at the admission desk. The one with the tiny font that you didn’t read. That is not consent. That is paperwork. Real consent is a conversation. It is a meeting of minds.

The law requires the doctor to warn you about “material risks.” A material risk is a big deal. It is a risk that would make a reasonable person think twice. If there is a 1% chance of death, you need to know. If there is a 5% chance of paralysis, you need to know. If the doctor stays silent because they don’t want to scare you, they are breaking the law. Paternalism is dead. They cannot treat you like a child who needs to be protected from the truth.

The shift to patient-centered consent

For years, doctors decided what you needed to know. If most doctors didn’t mention a specific risk, the court said that was fine. The medical profession set its own rules. That changed. South African law moved to a “patient-centered” test (Castell v De Greef).

Now, it doesn’t matter what the doctor thinks is important. It matters what you think is important. If you are a pianist, a 1% risk of stiff fingers is huge. To a plumber, it might not matter. The doctor has to look at you—the specific human being in front of them—and explain the risks that matter to your life. If they fail to do that, and the risk happens, they are liable. Even if they performed the surgery perfectly. They are liable because they didn’t give you the choice to say “no.”

“The Thing Speaks For Itself” (And Why It Usually Doesn’t)

There is a Latin phrase lawyers love. Res Ipsa Loquitur. It means “the thing speaks for itself.” In some parts of the law, it is a shortcut. If a barrel of flour falls out of a warehouse window and hits you on the head, you don’t have to prove how it fell. Barrels don’t just fall. The warehouse owner is guilty unless he proves otherwise. The accident itself is the proof.

Victims of medical negligence love this idea. You wake up from stomach surgery with a cut on your leg. Surely, that speaks for itself? Surely, the doctor has to explain it? In South African medical law, the answer is usually no. Our courts hate this rule in medical cases. They almost never use it.

Why you can’t just point at the injury

The court assumes medicine is complicated. They assume that strange things happen in the human body without anyone being at fault. If they allowed Res Ipsa Loquitur, doctors would be guilty every time a surgery had a weird outcome. So they forbid the shortcut. You cannot just point at the cut on your leg and say, “Explain this.” You have to prove exactly how the cut happened. You have to prove the doctor was holding the knife. You have to prove he slipped. You have to prove he wasn’t looking.

The burden of proof stays on you. Heavy. Unfair. The doctor can stay silent. If you can’t explain the mechanics of the mistake, you lose. The “thing” does not speak. You have to speak for it. And you have to use science to do it.

The Brutal Reality of the Process

We need to stop talking about the law. We need to talk about your life. Because if you decide to sue, your life changes. You enter a tunnel. It is long, dark, and expensive. Most people are not ready for the sheer weight of litigation. They think it will be a quick fight. It never is.

Time

If you sue in the High Court of South Africa—which is where these cases belong—do not expect a result this year. Do not expect one next year. A medical negligence trial takes three to five years. Sometimes longer. The wheels of justice turn, but they grind slowly. Files get lost. Judges get sick. Lawyers ask for postponements because they aren’t ready. You will wait. You will wait while your injury heals or gets worse. You will wait while your memory fades. It is agonizing. It feels like the system is ignoring you. It isn’t personal. It is just bureaucracy.

Money

Justice is not free. It is a luxury product. To run a trial, you need a team. Senior advocates. Junior advocates. Attorneys. Five or six medical experts. The bill for a single day in court can run into tens of thousands of rands. Most victims cannot afford this. So they sign contingency fee agreements. “No win, no fee.” This sounds great. But read the fine print. If you win, the lawyer takes a huge cut. Usually 25% of your payout, plus VAT. That is a quarter of the money you needed for your future medical care. Gone.

And if you lose? You might not pay your own lawyer. But the court can order you to pay the other side’s legal costs. That can bankrupt a family. The risk is real.

The emotional cost of being cross-examined

This is the part nobody warns you about. You will have to testify. You will stand in a box. A stranger in a gown—the defense advocate—will stand up. His job is to destroy your story. He is paid to make you look like a liar. He will question your memory. He will suggest you are exaggerating your pain. He will dig into your past. He will look at your Facebook posts to see if you went dancing when you said you were crippled.

It feels like an attack. It feels like they are victim-blaming. They are. It is part of the game. You have to sit there and take it. You have to stay calm while they dismantle your dignity. It leaves scars that money cannot fix. If you are not ready for that, do not walk into that courtroom.

The Final Decision

This article was probably hard to read. Maybe it made you angry. Good. You need that anger to be cold and sharp if you are going to survive what comes next. The legal system is not designed to heal you.

It is a machine that weighs facts against rules. If you feed it emotions, it will chew you up. But that does not mean you should walk away. If a doctor was truly negligent, if they were sloppy and reckless, they must answer for it.

You just need to know the price of that answer. It will cost you sleep, privacy, and peace of mind. Only you can decide if that price is worth paying. If you are ready to fight, do not look for a lawyer who promises you millions.

Look for a lawyer who looks at your file and sighs. Look for the one who tells you the weak points in your case first. Find someone who values the truth more than your retainer fee. Ask them the hard questions we discussed here. If they can answer them without flinching, then—and only then—sign the mandate.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. I signed a consent form before the surgery. Does that mean I signed away my rights?

No. You consented to the surgery and its normal risks. You did not consent to negligence. If the doctor was sloppy, that form does not protect them. A piece of paper cannot erase their duty to be competent.

2. The doctor said ‘I’m sorry’ after the operation. Is that an admission of guilt?

Not necessarily. Doctors are human. They might be sorry you are in pain. They might be sorry the outcome was bad. That is empathy, not a confession. In court, their lawyer will argue they were just being kind. Do not rely on an apology as proof.

3. How much money can I actually get?

Nobody can answer this without doing the math. It is not a lottery. You get paid for what you lost. Past medical costs. Future medical costs. Lost wages. General damages for pain and suffering. If you can still work, the payout will be lower. If you need 24-hour care, it will be higher. Anyone promising you a specific number today is lying.

4. It has been four years since the operation. Is it too late to sue?

Maybe. The general rule is you have three years from the time you knew (or should have known) about the negligence. This is called “prescription.” If you missed the deadline, your case is dead. There are exceptions—like if the patient is a child or mentally incapacitated—but you are walking on thin ice. See a lawyer immediately.

5. I don’t have money for a fancy lawyer. What do I do?

Most medical negligence lawyers work on a contingency basis. “No win, no fee.” They pay for the experts and court fees upfront. If you win, they take a cut (usually 25% plus VAT) and get their costs back. If you lose, they lose their money. But be careful. If you lose, the court might still order you to pay the other side’s legal costs.

6. Can I just complain to the HPCSA instead of suing?

Yes. The Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) disciplines doctors. They can suspend a doctor or strip their license. But they cannot give you money. If you want compensation to pay your bills, you have to go to court. You can do both, but they are separate fights.

7. Why is my lawyer asking for my Facebook and Instagram passwords?

Because the other side will look at them. If you claim you have a “crippling back injury” but you posted a photo of yourself jet-skiing last week, your case is over. Your lawyer needs to know what ammunition is out there before the enemy finds it.

8. Why does this take years? Can't we just show the judge the X-rays?

The court diary is full. Getting a trial date takes months or years. Before that, you need reports from experts. Then the other side needs time to answer. Then the experts have to meet. It is a slow, bureaucratic grind. There is no fast lane.

9. My child was injured at birth. Does the three-year rule apply?

No. Prescription (the time limit) usually only starts running when the child turns 18. They have a year after turning 18 to sue. However, waiting 18 years is a bad idea. Records go missing. Witnesses die. Memories fade. It is harder to prove a case the longer you wait.

10. The hospital offered me a settlement quickly. Should I take it?

Be very suspicious. They are not a charity. If they are offering money fast, they know they are in trouble. They are probably offering you a fraction of what your claim is worth to make you go away. Do not sign anything until an independent lawyer reviews the offer.

11. Can I sue the State hospital?

Yes. But the State is a nightmare to litigate against. They are slow. They lose files. They often defend cases they should settle just because no one wants to sign off on the payment. You need a lawyer with specific experience fighting the Department of Health.

12. What happens if the doctor dies or moves to Australia before the trial?

If they had insurance (medical malpractice indemnity), the case usually continues. The insurer steps in. If they were uninsured and have no assets in South Africa, you might be suing a ghost. You can get a judgment, but you can’t get blood from a stone.

13. Do I have to go to court? I don't want to see the doctor.

You almost certainly have to go. You are the main witness. The judge needs to hear your story. You need to be cross-examined. It will be uncomfortable. If you cannot face the doctor, you cannot run the trial.

14. My lawyer wants to hire five different experts. Is this a scam to make money?

Probably not. Medicine is specialized. An orthopedic surgeon cannot talk about your brain injury. A neurologist cannot talk about your future earnings—you need an Industrial Psychologist for that. You need an Actuary to do the math. If you skip an expert, you leave a hole in your case.

15. Can I fire my lawyer if I'm unhappy?

Yes. But there is a catch. Your old lawyer will have a “lien” on your file. They won’t hand over the papers to the new lawyer until their costs are secured. The new lawyer usually has to promise to pay the old lawyer out of the winnings. It gets messy.

16. What is a 'pre-existing condition'?

It is the defense’s favorite weapon. They will argue that your back pain isn’t from the surgery, but from an old rugby injury you had in 2010. They will try to prove you were damaged goods before the doctor touched you.

17. The other side sent me to their own doctor. Do I have to go?

Yes. It feels invasive, but they have a right to assess your injuries. They cannot defend themselves if they don’t know what is wrong with you. If you refuse, the court can stop your claim.

18. Will I have to pay tax on my payout?

Generally, in South Africa, compensation for personal injury (pain and suffering, medical costs) is not taxed as income. It is a capital receipt. However, if you invest that money and it earns interest, the interest is taxable.

19. Why did my lawyer drop my case after receiving the expert reports?

Because the experts said you would lose. Lawyers work on risk. If the medical expert says “The doctor did nothing wrong,” the lawyer cannot win. They are cutting their losses (and yours) before you run up a massive bill for a trial you can’t win.

20. Is it really worth the stress?

Only you can answer that. If you need the money to survive—to pay for care, therapies, or a wheelchair—then you have no choice. You have to fight. But if you are suing just for an apology or “justice,” the cost to your mental health might be too high.